The value of focusing your product team

The cost of simultaneously working on several topics and how to reduce them

When I am trying to push a singular focus during sprints or even for entire quarters, I have received plenty of pushback in my career. Focus implies that that we commit to one thing and decline an infinite amount of other options. Naturally, this triggers a fear of missing out.

This fear is fed by several misconceptions. First, a "no" at the moment must not be a "no" forever. It is just a definitive "no" right now. Second, doing more things doesn't mean you get more things done. More often then not the opposite is true. Third, we treat "slack" like it is something to be avoided and try to stuff our roadmaps and sprints. But actually planned slack, allows you to react to unplanned changes and new insights.

When researching why tackling mutliple topics in parallel hurts productivity I found that the crux is understanding switching costs.

Switching Cost and overhead - the expensive price for multitasking

Everyone whose profession requires some kind of deep work has experienced this himself. You are currently focused on working on a complicated topic, like an essay, a piece of code, or the presentation for the next board meeting. You progress consistently until a bing from your messenger confronts you with an urgent problem from a customer that requires your immediate attention. After you extinguished the major fires, you return to your previous work. Instead of seamlessly picking up where you left off, you likely found yourself stuck for 10 minutes or more trying to get a grip on the loose thread.

The reason for that is the switch in context. Your brain needs to invest energy and time to clear the mental ram and recall and refill it with the information of the former context. If this analogy is too technical, envision a desktop with loads of papers on it that you have to put away before you start to work on something else, so you can put all the stuff on the desktop that you need for your next task.

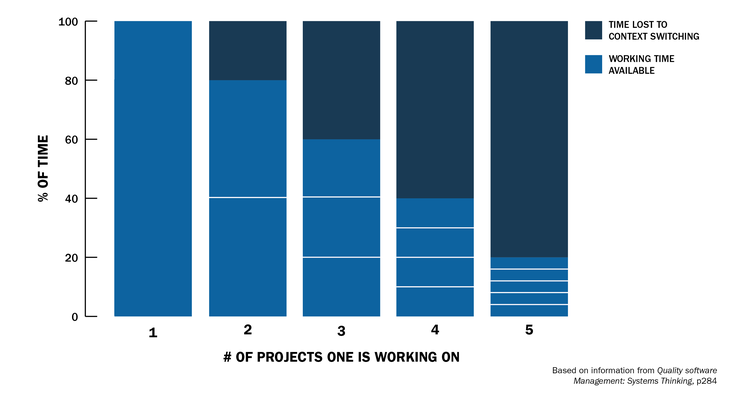

Some experts claim that these switching costs can take-up to 20% of available time with each additional project. Hence, when working on 4 projects simultaneously, we spend more time context switching than working on the actual project itself.

The origin of switching costs

The origin of these issues can be traced back to our human limitations. Humans are not build to multitask and our mental capacity is limited.

Based on over a half-century of cognitive science and more recent studies on multitasking (which is nothing else than rapid switching between tasks), we know that multitaskers do less and miss information. Efficiency can drop by as much as 40%. Long-term memory suffers, and creativity — a skill associated with remembering multiple, less common associations — is reduced.

When it comes to switching (not really trying to do two things at the same time but switching from one to the other), studies on distraction indicate that it takes an average of 15 minutes to re-orient to a primary task after a distraction such as an email.

Adding insult to injury, even in the rare case where we can focus, studies indicate that we can only keep up to four items “in mind”.1

So, our actual working memory is very limited, and this explains why most knowledge workers depend on todo-lists, project plans, and other systems to keep them organized.

The evil twin of switching costs: Project overhead

While the switching cost are paid mentally by individuals, project overheads are transactional costs on an organizational level. Overhead costs are created by all the efforts to report and align on ongoing projects. These are the alignments that you have to be in to “stay in the loop” about topics that should be handled but you know that they won’t be top on you list for some time.

Or all these updates where you are supposed to update on the progress of a project that hardly progresses at all, as it just one of many. These are all activities that are valuable in the sense of coordination but not in the sense of value creation. And unfortunately they take away scarce time that could be used for value creation.

So in an ideal world, I could stop with the obvious conclusion that wherever and whenever possible, limit the number of projects that are “work in progress” (WIP). Unfortunately, most of us are working in a system that makes it almost impossible to keep WIP small. So what now?

How to reduce switching costs when you can’t focus on a single topic

Let’s face it: Most of us working in product face an onslaught of different topics screaming for our attention. New features, retention, strategy, bugs, tech-debt, stakeholders, discovery, all of these tasks require the attention of the product trio continuously. So how do we reduce the negative impact of switching as much as possible?

Ruthless prioritization

Being very clear on “what is the most important task right now” helps. Needless to say that this also includes sticking to that decision until the task is complete. This works on an individual level (finish this presentation and ignore all other mails and messages until it is done) as well as on a team-level (having a single clear sprint goal). Simply saying “no” to more things already reduces the work in progress significantly for most people.

Cluster activities by domain and similarity

Switching cost increase with the distance between activities. If you investigate several bugs within the same component, switching costs are much lower than switching from your AWS cloud setup to optimizing the responsiveness of your web-app.

This idea aligns with common productivity advice to “batch-process” similar tasks and set up time-blockers to focus on one specific topic at a time.

Batch mundane tasks

Switching costs also increase with complexity. Switching between mundane tasks is very low-cost and can actually be a welcomed change. If you have ever done a "clean-up" sprint where you tend to tackle a bunch of small tech and usability debts, then this was probably this type of tasks. PMs might batch all kind of reporting and admin responsibilities in a similar way.

Use natural breaks to switch tasks

Re-engaging with the same task after a disruption is probably similarly costly as engaging with a different tasks. If there is a natural break either way e.g., lunch break or end of your working day, you might as well make the necessary switch then. For example, Elon Musk is said to divide his schedule so it’s predominantly one company on one day as “switching context is quite painful.”2

Document your last thought and next step

Whenever you are about to switch tasks, jot down your next thought or step. That way you will save a couple of minutes to pick up the thread when you return. Whenever I e.g. can finish up a new newsletter, I try to at least write out the next sub-headlines or some kind of instruction what I would do next to finish the article.

Increase the effort necessary to delegate task to you

To be fair: Good delegation is hard. Good delegation is also much more than the agreement that “someone should do something”. Insist that the task delegator provides sufficient information necessary upfront or that necessary decisions are made before you start on the task. By increasing the expected level of refinement of tasks, ideas or projects that are delegated to you, you will find that the urgency and importance of these quickly decreases. It’s almost embarassing how urgency and importance reduces whenever the delegating party is expected to do something first. From the other side it is somehow understandable that you try to declare every nice-to-have as urgent and important as long as you don’t have to do it.

Let’s say a sales manager approaches you with a feature idea and ends the pitch with the notorious question “Until when can you do this?”. By just claiming you need to discover it first, you already agreed to take on all the research on your own. Instead say something like this: “Sounds like an interesting idea. Can you write all that down in a brief, provide a list of at least five customers for whom this feature will be relevant and who are willing to jump on a call with us?”.

Even the small friction of asking the other to document the ideas in a written form is sufficient to stop some initiatives in their tracks. Ironic, that you were expected to develop the same feature for weeks! By increasing the effort required to delegate tasks to you, you introduce a first quality gate for what tasks end up on your desk after all.

Make your work in progress and roadmap visible

With at least some common understanding that less work in progress and more focus is better, make it clear and visible what you are currently working on. If you are exected to things now, make it clear that this also means that you stop to work on whatever you currently focus on.

Same works for whatever is next on your roadmap. I am not a huge fan of roadmapping but “Now-Next-Later"-Roadmaps” come in handy to communicate what I am currently doing and what I expect to do next. In this cases “Next” usually never extends to much more than the next 3 months. For me this is the time-frame I feel comfortable to communicate commitment and usually is aligned with the quarterly OKR planning cycle. Coveniently it is also a time frame where I feel like I can roughly estimate how much we can get done. So the list of next items is usually small enough to force and make a tradeoff decision.

If initiatives don’t make the “Next” list either, they get an honorable mention in the later column of the roadmap. However, I never comit that these initiatives will be pursued but make it clear that this will depend on future goals, priorities and competing initiatives.

Some of these tips might work better for you, others won’t.

Give them a try. Experiment with them. Use what works. Drop what doesn’t.

Increasing the focus of your team by just a little bit, is already worth the effort.

Buschman, T. J., Siegel, M., Roy, J. E., & Miller, E. K. (2011). Neural substrates of cognitive capacity limitations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(27), 11252–11255. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1104666108

https://www.cnbc.com/2023/05/23/elon-musk-splits-time-across-spacex-tesla-and-twitter-heres-how.html