Strategic skill acquisition

When to focus on your strengths and when to tackle your bottlenecks

So if you are only 5’4” (160cm) you should not try to become a basketball player, as taller people will likely be better than you with a fraction of effort.

This analogy represents the ruling trend of a strength-focused approach to skill acquisition. Proponents of this approach argue that one should primarily focus on what one is naturally good at to leverage “god-given” talents. That way, one's return on learning investment might push one into the world's top class. On the other hand, focusing on one's natural weaknesses would get you to a mediocre level at best. There is a German saying that you can’t turn a plowhorse into a racehorse.

For most professions, skill is usually not measurable on a single scale

This line of thought also assumes that “skill” and its utilization depend on a narrow scale. E.g., a golf player’s skill to hit a ball where he intends to hit it will determine if he is a good player. The same is true for mastering an instrument. These professions also have in common that the top that can make a good living is very small. Only a tiny fraction of piano enthusiasts will become concert pianists who can make a comfortable living. The great majority will have to downgrade their aspirations to a hobby. The same goes for most athletic endeavors.

Most knowledge worker professions, however, are less unidimensional. What makes a great leader or manager? That’s a question that inspired entire libraries of books. It is not a single skill but a combination of countless skills determining your effectiveness.

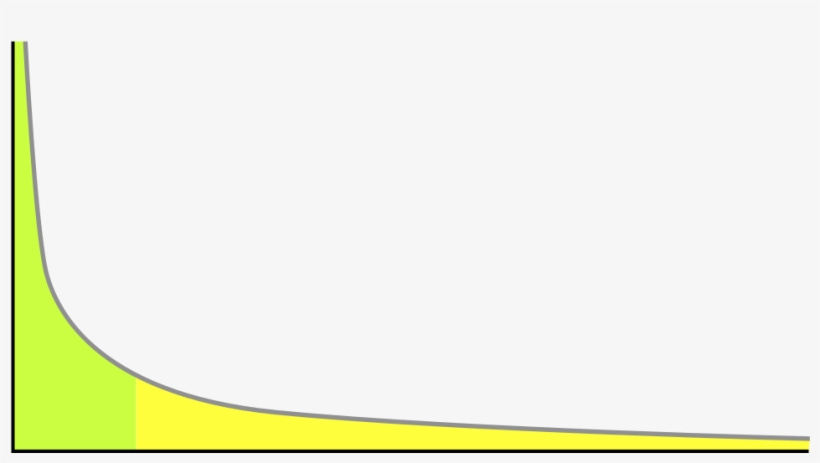

Instead of a single skill, we need to think of skill stacks and the combination of skills. This doesn’t mean that deep expertise in a single domain is worthless, but on a pragmatic level, I have found it to have diminishing returns in most contexts. At the same time, smart skill stacking can deliver exponential returns.

People like me, who have trouble identifying a single passion, can use their curiosity to strive for an extraordinary combination of skills instead of becoming extraordinary in a single skill.

Skill is context-dependent

In addition to that, effectiveness is highly dependent on context. A start-up requires different management and leadership approaches than a large corporation. Certain skills do not transfer well between different company cultures; others do. This insight is a warning and encouragement at the same time. We might be over-confident in our skills if we don’t realize that our effectiveness has been increased by the context in the past. E.g., colleagues that perfectly filled your deficiencies or that you have been welcomed to fill a void such as a lack of leadership. Without these colleagues and a request to align with current leaders, you might find yourself ineffective after all.

But this is also an encouragement to find a different pot in case you find you can’t bloom in your current one.

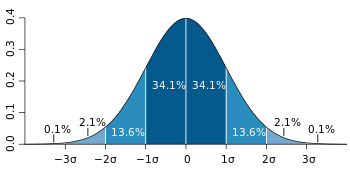

Skill doesn’t follow a Gaussian distribution

When discussing skill and skill distribution, we pretend that skill follows a Gaussian distribution. This means most people are okay; half are poorer than that, and half are better than that.

I think skill is more often distributed according to a power law distribution. That means the majority, and that is up to 80%, sucks at a skill. You might not perceive it that way as you are in a bubble of peers with similar interests and motivations. My rudimentary knowledge of HTML, CSS and javascript doesn’t make me an expert developer and even an equal to the developers I work with daily. But 80% of people have never even tried to touch code.

Sadly, most people are not interested in getting better at something, so they don’t even try. No one was born a master. Taking a few steps on the mastery journey will be sufficient to get you in front of the pack, that is, most people. You probably won’t be a world-class and recognized expert, but that’s okay. The newly acquired skills can open up new opportunities either way.

Tackle bottlenecks or multipliers, regardless of your talents

It’s okay to have weaknesses. And it is fair to say that you should not tackle a weakness if you can compensate or circumvent it. If you have no nag for coding, but there is absolutely no need for you to do so, why go at it?

If your weakness is an absolute bottleneck, it’s a different game.

For example, I am not naturally structured. However, I found that my lack of structure hampered my productivity and my ability to delegate and communicate. I worked hard to become more structured, which paid off tremendously. Even though I still have room to grow, I am past the point where it hurts my effectiveness.

The same goes for multipliers. Sometimes, skill gaps don’t hurt, but closing them would have an outsized return on investment. Technical experts who add people management to their skill sets often experience outsized returns through their career progression.

The often-cited advice, “Don’t bother working on your weaknesses; you will never be great at them no matter how much work you put in them,” is true in essence but poor advice. You might not become great at it, but you will be good enough. Good enough so it does not hamper your effectiveness.

In defense of deep expertise

So when skills become more valuable by stacking them, and you can get into the top 10% in relatively short periods of time, is deep expertise still valuable? Is it really worth the effort to inch towards the top 1%, top 0,1%, or even further when facing diminishing returns?

I believe it is. Regardless of the craft, people at the pinnacle get paid handsomely and often find more meaning in their work. Achieving mastery is fulfilling personally and professionally. Sticking it out and truly investing the work necessary, even to get close to mastery, is extremely hard - so most people give up. That’s why true experts are so rare.

So, if you want to add that to your mix, you need to make sure that you have sufficient love for the subject to go all the way.